Medieval Accounting

The general principles of double-entry bookkeeping were created in thirteenth century Italy and fully developed by the fifteenth. Still in use today, these principles remain largely the same.

The ledgers that we have calendared were Libri di debitori e creditori (Debtors and Creditors) ie the ‘final’ ledgers, in the sense that they were the product of a series of other preparatory books, such as journals, day books, books of merchandise, books of commissions, cashbooks, etc.

Double-entry bookkeeping

The general principles of double-entry bookkeeping were created in thirteenth century Italy and fully developed by the fifteenth. Still in use today, these principles remain largely the same.

How it works

Each transaction is recorded twice, with one account being debited and another credited.

When an account is debited, the transaction is recorded on the dare (left) side; when credited, the transaction is recorded on the avere (right) side.

As this system reflects the account-book holder’s point of view (ie, the Borromei bank’s), an amount recorded on the debit side means that the client is in debit towards the bank by that amount (the client deve dare, ie, must give). Conversely, an amount recorded on the credit side (the client deve avere, ie, must have/receive) means that the client is in credit towards the bank.

Two examples from the account of Ubertino de’ Bardi & Partners in the Bruges ledger show how this worked in practice. On 3 May 1438 the bank paid Anichino, the Bardi’s valet, £49 flemish at the fair at Bergen-op-Zoom. This increased the amount the Bardi owed the bank and so appears on the debit or dare side of their account at f. 52. As it was a cash payment (money going out of the bank’s own coffers), the parallel transaction appears in the account for Cash at Bergen-op-Zoom on the avere side. In other words, if the bank pays the Bardi in cash, the transaction is recorded in the dare of Ubertino de’ Bardi & Partners, and in the avere of the Cash account.

Most transactions, however, were ‘mere’ book transfers (giri di partita), with no cash changing hands, just verbal or written orders to the bank.

Keeping the ledgers

A client could have more than one account. They had one current account which might appear only on one folio in the ledger, carried forward sometimes to another folio whenever the accountant ran out of space. If there were only a few entries left to be made, then they could be continued on the opposite side of the page, if there was room, and after separating them with a horizontal line. This is why on the avere-side folio debit entries are sometimes found, and vice-versa.

More established clients usually had several different accounts: a current account, an account for a specific purpose (a ‘conto a parte’), a trading account to buy or sell wool, cloth, madder and other commodities. Moreover, in certain moments, the bank and the client could agree on the outstanding balance, close that account, and immediately open a new one (conto nuovo).

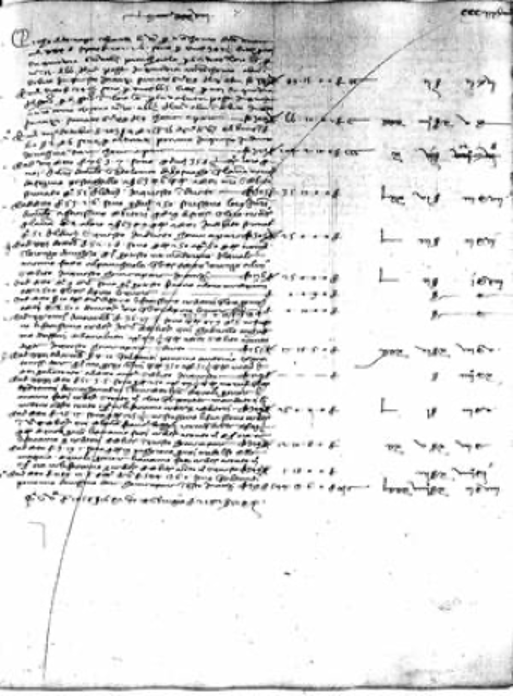

Clients (normally other companies of merchant-bankers) located abroad had a nostro and a loro or vostro account, the former being an account kept abroad by a client for the bank itself in a foreign currency and the latter an account kept in Bruges by the bank for clients based elsewhere. The bank would record each entry with two currencies, their own (in our case £ flemish or £ sterling) and the foreign currency in to different columns, as in the example below, where the first is kept, using hindu-arabic numerals, in the £ venetian, the second, using roman numerals, in the £ flemish.

In theory, at any given moment, the sum of all the debit entries on the dare side should equal the sum of all the credit entries on the avere side. Unfortunately, various mistakes could happen, and sometimes remained undetected: we have indicated when this was the case. Sometimes, however, the accountant spotted certain types of mistakes: eg when he had debited or credited the wrong account, he wrote a new record on the opposite side to cancel it, and then a new one in the correct account. Occasionally, the cross-entry for one transaction was recorded in another book (eg the libro segreto, secret book), thus undermining the perfect balance of the ledger.

Upon scrutiny, if the account balanced, it was crossed through, with a single slash, on both the dare and avere sides.

Both in Bruges and London at the end of each calendar year (31 December) the ledger was closed: balances were carried forward to a new ledger on 1 January.

Money of account

The Borromei ledgers shows that accountants or book-keepers were faced with a multiplicity of coins and currencies, Flemish, English, Venetian, Milanese, Florentine, Rhenish, Genevan. The solution to a problem common throughout western Europe was to use money of account.

The most common dictionary definition of money of account is ‘a monetary unit in which accounts are kept that may or may not correspond to actual currency denominations.’ This was based on the old Roman system of pounds, shillings and pence, libra, solidi, denari or denarii. There were 240 pence or pennies to the pound, 12 pence to the shilling and 20 shillings to the pound. The only one of these denominations that actually existed was the penny, specifically a silver penny. The other two were accounting units only. The face value of all other coins, silver or gold, was related to the penny. The Flemish groat was worth four silver pennies or groschen and the Flemish gold écu was worth 24 groschen, the English groat 4 silver pennies or sterlings, the English gold noble 80 sterlings or 6s 8d, the Venetian ducat 24 grossi and so on. There were no pound coins: it was simply a unit of account.

Translating and calendaring ledger entries

In both London and Bruges the ledgers are kept in “Italian’. Translating every record in English did not seem the most appropriate way, as sometimes parts of the registrations are obscure in their meaning and in other instances a literal translation would simply be unintelligible for an English-speaking audience. For example, even ‘simple’ journal entries can generate some uncertainties, when many parties are involved. Although it is clear who is debited and who is credited, other parties (non account holders) could be involved in a payment as intermediaries between the bank and its clients. The Italian word ‘per’ has multiple meanings in English (for, on behalf, through) making it complicated to grasp each person’s role in the transaction.

The English versions had to mirror the Italian and show clearly and concisely how and why the money was being debited or credited from one account to another.Where possible, the Italian word order has been followed but in some cases that was neither practical nor desirable. We therefore decided to translate the plainer and more narrative registrations and on the other hand calendar/summarise those more convoluted, preferring to favour clarity in place of a rigid philological criterion.

Moreover, in some instances – notably bills of exchange – we decided to present the transaction in a schematic way (with the clear identification of the parties involved and of their role) because the ‘simple’ translation would be difficult to interpret by those who are not acquainted with late medieval finance. Therefore, for example, a transaction as follows,

Ubertino de’ Bardi e compagni deon havere … sono per una lettera ne fecie a Barzalona di scudi 800 a s7 d5 per scudo per dì 65 fatta insino a dì 5 di questo in Antonio de Pazi e Francesco Tosinghi i quali rimettemo a Bernardo da Uzano e compagni per loro conto a loro, fo 168

has been inputted as

Bill of exchange for sc. 800 at s.7 d.5 per sc.

Deliverer: Borromei Bruges

Taker: Ubertino de' Bardi & co. of Bruges

Payor: Antonio de' Pazzi and Francesco Tosinghi of Barcelona

Payee: Bernardo da Uzzano & co.

Letter written: 5 February. Settlement date: 65 days from date [11 April]

At Uzzano & co., f. 168

rather than as a less intelligible literal translation:

Ubertino de’ Bardi and partners must have ... for one letter written for us to Barcelona, for sc. 800 at s7 d5 per scudo, for [settlement date] 65 days after writing, on the 5th of this [month], [drawn] on Antonio de’ Pazzi and Francesco Tosinghi, which [sum] we delivered to Bernardo da Uzzano and partners, loro conto, at their [account], fo 168

For the sake of clarity, three basic principles have been followed. Material in round brackets in the text of any entry is original, that is, it appears in Italian in the ledger entry. It has been entered in this way for the sake of convenience or where there is doubt about a particular word or name. Square brackets signify editorial additions or notes. One of the two (cross-)entries often contains more information than the other and that has either been added to the text or cross-referenced, in square brackets. Original errors have also been noted in this way, be they differences in dates or exchange rates, or others. Lastly, editorial doubts have always been indicated by question marks.

Users who are more acquainted with late-medieval Italian accounting can pursue these doubts further by consulting the digital image of the account or entry in question. Users obviously have the possibility to check the original document.