Reflections on a Participatory Research Practice-Sharing Event

Bonus Blog Post! On 30 October 2024, the Centre for Public Engagement hosted a dynamic practice-sharing event on participatory research, co-led by Dr. Aoife Sadlier (QMUL) and Chelsea McDonagh (Young Foundation). Drawing on insights from lived experiences and the principles of participatory research, attendees explored successes, failures, and the realities of co-creating knowledge.

As Vaughn and Jacquez (2020) describe, participatory research involves researchers working with communities that are not necessarily trained in research but that are impacted by the topic under study, to drive for action and change. With its roots in Kurt Lewin’s action research in the UK and US, which advocated for enquiry, action and evaluation, and the work of scholars such as Oscar Fals Borda in Latin America, which sought to empower marginalised people and develop social movements, participatory research has evolved to become an engaged and meaningful mode of research.

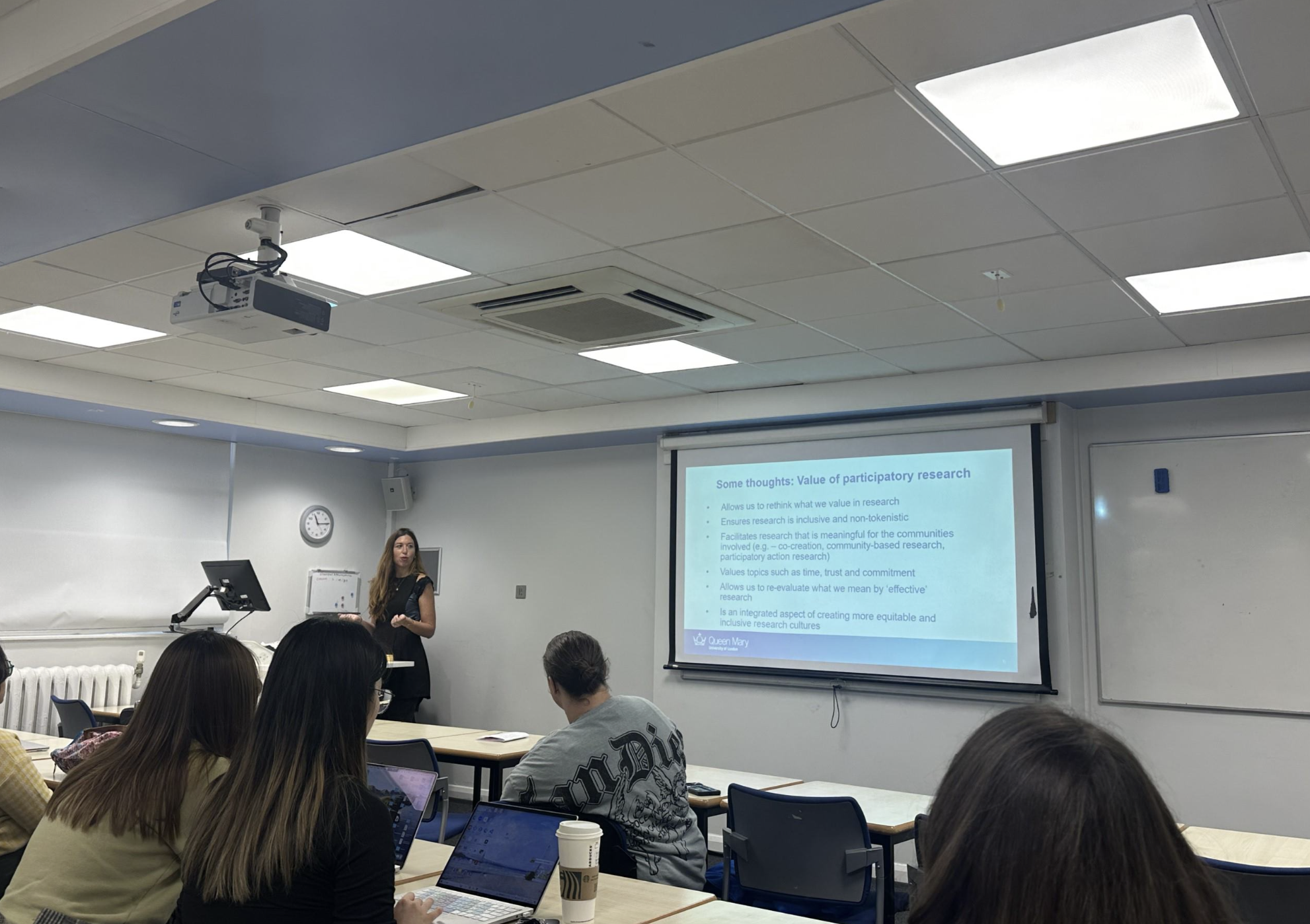

At the practice-sharing event, researchers with expertise and experience in co-leading and working on participatory research projects, from across different departments and faculties at QMUL, were offered the opportunity to gain insights into QMUL’s annual Participatory Research Fund; share examples from their own research; and network with other participatory researchers, with the potential for future collaboration.

The day began with an introduction delivered by Dr Sadlier, followed by a presentation by Dr. Giorgia Michelini, a former Participatory Research Fund recipient. Dr. Michelini described her team’s project on the barriers neurodivergent young people face when accessing mental health services. Dr. Sadlier and Chelsea McDonagh then went on to facilitate interactive sessions on successes and failures in participatory research. The discussions drew inspiration from Jancovich and Stevenson’s (2023) open-access book, Failures in Cultural Participation, which encourages us to re-evaluate what success and failure mean with our participatory research hats on.

Participants engaged in lively discussions about the value of participatory research: its roots in participants’ lived experiences; its positive impacts on participants regardless of research outcomes or outputs; the learning process inbuilt; and the power of finding new ways of working that go beyond traditional academic approaches. Ultimately, the discussion highlighted the power of enabling marginalised groups to gain voice, on their own terms.

Perhaps most pertinent were the insights shared concerning the elephant in the room – that dreaded word ‘failure’. Participants often felt hemmed in by funding constraints and expectations – the need to adhere to strict budgets and to deliver outputs within a certain timeframe – when in reality, participatory research involves an extended period of trust-building with communities. This in turn requires time and commitment, two aspects that aren’t always valued by the academy. The process can be messy and doesn’t always run like clockwork. Any perceived failures in a sense emerge because traditional academic research culture is not fully ready to accommodate participatory research, which is premised on process rather than outcome.

Other thoughts on failure included institutional issues with paying members of the community. If payment processes do not work then this is harmful not only for participants themselves, but also for the researcher/participant relationship and institutional reputation. Proposed solutions included usage of a platform called Ayda to organise payments in a fair and systematic manner.

Another vital point discussed is the tendency to refer to research as ‘participatory’ when participants have not been actively involved throughout the research process; in this way, the design isn’t always inclusive. Indeed, some argue that participatory research has become no more than a tokenistic buzzword to support the Research Cultures drive for REF, without the necessary structures being in place to support its implementation. What is arguably needed is a shift in values. The discussion led to further musings on reorientating what we mean by ‘failure’, ultimately calling us to ask ourselves, in the words of Jancovich and Stevenson (2023, p. 49): ‘Success and failure for whom? In what ways? To what effect?’.

Drawing on the words of the literary great, Samuel Beckett, in Worstward Ho, we need to: ‘Try again. Fail again. Fail better’. Ultimately, to fail better, we need to make mistakes, because otherwise no real learning will be gained. Learning means taking risks, and ultimately, looking out for each other on the long and lonely road that participatory researchers often seem to traverse within existing HE structures.