‘China and the West’

Chinatown Lower East Side of Manhattan looking towards Kimlau Square from the walkway on the Manhattan Bridge

Suman Gupta is Professor of Literature and Cultural History at the Open University.

English-language media have aired an intensifying rumble of anxious deliberations on ‘China and the West’ over the last decade. The phrase’s associations seem all encompassing, stretching across political, economic, cultural, technological, military, and other domains. It appears to be a fulcrum for much commentary on or related to China.

By way of reflecting on it, let me begin with the implications of the phrase itself – specifically in English − and turn to its contexts thereafter.

Usage

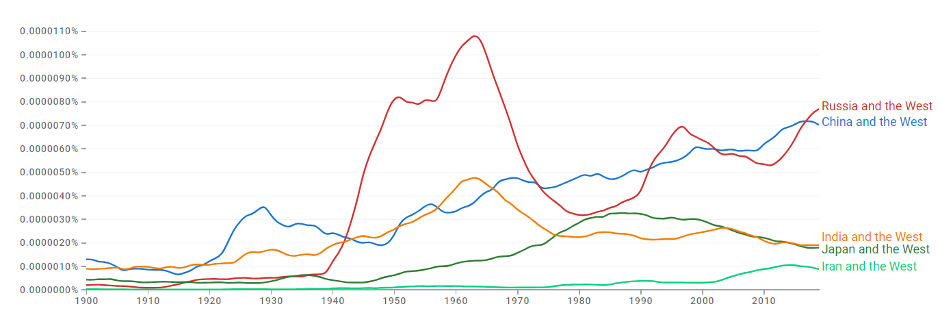

Judging by Graph 1 (click to view the full-size graph), for well over 100 years the phrase ‘China and the West’ has been used with reasonably high and generally growing frequency. Compared to other analogous phrases, only ‘Russia and the West’ has had significantly greater purchase over the extended period 1939-1980, and then again through the 1990s, with usage-frequency fluctuating wildly otherwise. Over two brief periods ‘India and the West’ overtook it, in 1943-1950 and 1957-1965.

Graph 1: Google Ngram for ‘China and the West’, ‘Russia and the West’, ‘India and the West’, ‘Japan and the West’, ‘Iran and the West’, 1900-2019, Corpus: English (2019), smoothing: 3. The British and American parts of the English corpus together have around 190 billion words, from printed texts digitised in the Google Book corpus. The frequency measurement on the Y-axis is percentage of the word/phrase occurrence in the whole corpus; the X-axis shows the year in which works in the corpus were published.

These comparative shifts appear to match political junctures of global interest: 1939-1980 covers precisely the period of the Second World War and the height of the Cold War; the 1943-1950 period was the lead up to India’s Independence; 1949-1957 saw the establishment and consolidation of Communist government in China; 1957-1965 was the period of the Sino-Soviet Split and the Sino-India War; the 1990s saw the breakup of the former Soviet Union and its sphere of influence.

Insofar as we are focusing on the phrase ‘China and the West’, it is of some interest that it first caught on significantly in 1915-1929. I come back to this below. The long trajectories of ‘Russia and the West’ compared to ‘China and the West’ are of considerable interest and worth addressing in a separate essay.

Obviously, the phrase ‘China and the West’ constructs a binary perspective, as if the two sides are mutually constituted by differentiation or opposition. In that sense, the phrase appears to put two sides on a par with each other. It thus seems analogous to ‘East and West’, ‘Orient and Occident’, or more recently ‘Global North and Global South’. The latter are much discussed spatial or directional binaries, formed through histories of settlements and wars, colonialism, and the Cold War (e.g., Blair 2000, Brennan 2001, Hoerning 2023).

But ‘China and the West’ does not fit comfortably with those. Those binary terms juxtapose two mutually defined sides meaningfully; ‘China and the West’ obviously doesn’t. On the one side is the name of a single formation, ‘China’ (however conceived, whether in ethno-nationalist or state territorial terms); on the other side is a collective of formations under one referent, ‘the West’ (usually foregrounding Northern American and Western European countries). More precisely then, in the phrase ‘China’ seems to represent something larger than itself. It seems to be used as a synecdoche: perhaps a crystallization of ‘the East’ or the special other that represents ‘the East’ generally. In fact, the phrase has come to suggest that China presents a pinnacle of difference from ‘the West’. China is a sort of norm of Eastern difference which puts other lesser differences across the East into perspective.

There are many sources which present that idea of China’s normative difference from ‘the West’, some of which I mention later. For an immediate demonstration of how this works almost automatically, it’s worth checking out an interesting paper by John Blair, ‘Thinking through Binaries’ (2000). The first part describes how ethnocentric perspectives are centred in cartography; the latter discusses East/West binaries. In the latter, a Chinese concept of change is highlighted to demonstrate the workings of the binary construction. Blair takes it for granted that a Chinese concept will make this point emphatically, and it in fact seems to.

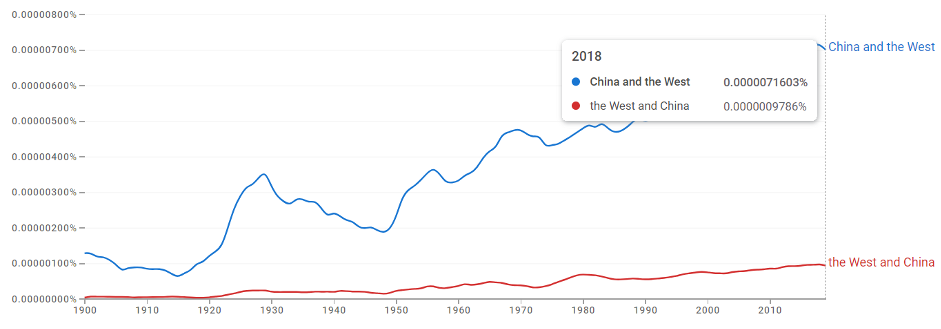

Turning to another aspect of the phrase: the usage is familiarly ‘China and the West’ and not ‘the West and China’. Though usage of the latter has crept up, it doesn’t sound right. Graph 2 (click to view the full-size graph) compares the two.

Graph 2: Google Ngram of ‘China and the West’ and ‘the West and China’, 1900-2019. In 2019, the former was used more than 7 times more frequently than the latter.

This sequence of words in the phrase has a bearing on how its implicit perspective – the subject-position – is suggested. The sequence of words has different emphases in English and Chinese. In English, ‘China and the West’ naturally inclines towards the perspective extended from ‘the West’. This is consistent with the convention of putting the subject-position later, as in ‘you and I’/‘them and us’. However, the Chinese equivalent ‘中国与西方’ (zhōngguó yǔ xīfāng), which has the words in the same sequence, naturally puts the subject-position on 中国 (China) and extends the perspective from there. This is because 中国 (zhōngguó) means ‘Middle Country’, which presents a centred location in terms of which other locations, in different directions, can be seen and gauged. This difference of perspectival emphasis in the phrase ‘China and the West’ and ‘中国与西方’ may make for distinct traditions of conceptualization and application.

It would be interesting to compare the traditions that have developed around ‘China and the West’ in English-language texts and ‘中国与西方’ in Chinese-language texts. The extent to which these coincide, overlap, and are distinct could explain much about geopolitical and cultural relations. However, I stick to the English phrase here.

1920s Contexts

I would like to suggest that the sudden rise in usage of ‘China and the West’ through the 1920s (see Graph 1) introduced certain associations which have remained with it despite the sea changes that the phrase has accommodated since.

The late 19th century phrase ‘Yellow Peril’ inserted an absolute racist wedge between Chinese and ‘White’ peoples in Europe, North America, and Australia. It captured the growing anti-immigrant prejudice in those contexts and bolstered colonial capitalist expropriation in China. ‘Yellow Peril’ racism has lingered with ups and downs through the 20th century. Madeline Y. Hsu (2015) found that in the USA ‘Yellow Peril’ racism had reversed by degrees after World War 2, so that Chinese immigrants began to be regarded as ‘good’. However, Christopher Frayling (2014) had no difficulty spotting it in international coverage of the Hong Kong handover in 1997. Such racism had an unabashed revival with the COVID-19 crisis (see Jack-Davies 2020, Siu and Chun 2020, Zarni 2023).

The newspaper reports, magazine and journal articles, popular and scholarly books on ‘China and the West’ that were produced prolifically in the 1920s were mostly intended to work against ‘Yellow Peril’ racism. Through these, the phrase gradually became formulaic. These publications started appearing sometime after the Boxer Rebellion, in view of the rise of Nationalist and Communist organisations, the New Culture Movement, and the brutalities of the Warlords Era. These were largely sympathetic engagements with the Chinese peoples’ emerging social aspirations and anticipated China’s imminent geopolitical significance. Their authors were usually critical of the destructive incursions of colonial powers in China – Western European, American, Russian, and, with particular opprobrium, Japanese. They argued for greater understanding between Chinese and European/North American peoples and hoped for political accord and international alliances. However, in pleading for cultural understanding, they magnified ineluctable difference; and in arguing for political understanding, they seemed to be raising the spectre of antagonism. ‘China and the West’ came to suggest liberal goodwill against the odds – therefore, a compromised liberalism.

An extreme culmination of ‘Yellow Peril’ racism and, at the same time, an anticipatory nod towards ‘China and the West’ liberalism, came in Jack London’s short story ‘The Unparalleled Invasion’ (1910). This was presented as a future historical document recording past events, and was premised on the incommensurable difference of ‘psychological speech’ in Chinese and Western thought. The narrative describes how the world came to be overwhelmed by China’s burgeoning population and emigrations and by its self-propagating modernization introduced via Japanese imperialism. The narrative effectively extended logically from ‘Yellow Peril’ delusions. The logical culmination consisted in China being put under siege by a USA/Europe-led alliance, and then its population being annihilated with biological weapons. The story was all the more chilling in presenting plausible (and as it turned out, prescient) inferences about international moves around China over the next couple of decades. London’s story could be taken as viciously xenophobic or as performing a reductio ad absurdum that reveals the anti-human/inhuman abyss at the bottom of such xenophobia (for careful readings, see Swift 2002 and Métraux 2008). It represented, in any case, an exhaustion of the ‘Yellow Peril’ discourse. There’s nothing beyond this vision unless one takes a searching look at what lies between ‘China and the West’ – the strains of which could be traced back to Jesuit accounts, from the 16th century and onwards.

To give a brief sense of the ‘China and the West’ direction as it emerged in the 1920s, I refer to two representative and influential books: Bertrand Russell’s The Problem of China (1922) and W.E. Soothill’s China and the West (1925).

Books like Russell’s (1922) and Soothill’s (1925) were designed to explain the contemporary position of China to ‘Western’ readers. First-person pronouns and concordant modes of addressing readers consistently positioned the texts within the ‘Western’ perspective. Russell naturally took a broadly cultural and political view, sweeping in scope; Soothill (then Professor of Chinese at Oxford University) gave a historical summary or ‘sketch’. Both were critical of the destructive record of European, American, and Japanese colonialist activity and trade in China. Both were hopeful of China’s future rise in global eminence and independent development while absorbing the more salutary aspects of ‘Western’ knowledge. Both had direct experience of life in China – Russell in a small way over a lecture-teaching tour in 1921-1922, Soothill very much more substantially over 38 years as a missionary and then an academic.

Both were written with two similar thrusts.

First: prospects for exacerbated discord between ‘China and the West’ occupied both authors – the spectre of China as a potentially powerful antagonist. These accounts were driven by a desire of counter such a possibility from the ‘West’. Russell (1922) hoped China would not become ‘Westernized’ into another ‘restless, intelligent, industrial, and militaristic nation’; at the same time, he worried that ‘they may be driven, in the course of resistance to foreign aggression, into an intense anti-foreign conservatism’ (13-14). He concluded with a warning against China becoming aggressive in a ‘Western’ mould once foreign aggression is overcome (251-52). Soothill’s (1925) account was straightforwardly historicist, but the final two chapters turned to the present with similar misgivings. He was convinced that a ‘renaissance will come’ in China soon (194); and argued strenuously that there really aren’t (or shouldn’t be) ‘any unfriendly feeling’ on either side towards the other. He ended, as befits a former missionary, with a prayer that ‘East’ and ‘West’ will solve the problems of living ‘together for each other’s welfare’ in a ‘spirit of goodwill’ (200).

Second: in a curious way, the call for understanding between ‘China and the West’ was premised on ineluctable if not incommensurable difference. The attitude was ironically not miles away from the incommensurable difference of ‘psychological speech’ in London’s story. It appeared that understanding China’s current political and economic circumstances calls for an understanding of all of China’s history, all of its cultural forms, and all of its socio-psychological features – in fact, a chasm of essential difference needs to be crossed. The sort of engagement with material realities, political and economic calculations, principles of social organisation and everyday life that apply to other countries would not be enough when confronted with China. So, sweeping generalisations on Chinese psychology, ethnos, (Confucian) values, historical accretion littered both Russell’s and Soothill’s books. In both books, present-day and on-the-ground realities seemed to get lost amidst civilizational dichotomies and totalising generalizations. In fact, most 1920s ‘China and the West’ studies suggested that what’s involved is nothing less than a confrontation with the totality of their ‘Chinese civilisation’ from amidst the totality of our ‘Western civilisation’. Occasional critiques of such ‘civilizational’ totalities were to appear only from the late 20th century onwards (e.g., Patterson 1997, Bonnett 2004, Ferri 2021).

Reference to two books naturally makes for excessively schematic observations on the 1920s ‘China and the West’ publications. A systematic study of more of these may offer a nuanced or revised picture. Such a study would also look to similarly well-informed or scholarly books like: E.T.C. Werner, China of the Chinese (1919); Gilbert Reid, China, Captive or Free? (1921); Paul Hutchinson, China’s Real Revolution (1924); Putnam Weale, Why China Sees Red (1924); James H. Dolsen, The Awakening of China (1925); Walter H. Mallory, China: Land of Famine (1926); Arthur Ransome, The Chinese Puzzle (1927); G.N. Steiger, China and the Occident (1927); John Earle Baker, Explaining China (1927); Louis M. King, China in Turmoil (1927) … to name a few. And a multitude of popular books, news reports, scholarly papers, feature films, etc. would need to be considered. There were also numerous accounts by Chinese scholars writing in English or available in English translation.

Now

Tracking iterations of the phrase ‘China and the West’ in the hundred years since the 1920s would be a vast project. We may expect the phrase to register various momentous social shifts in the interim, with changing connotative balances and associations. At the least, the Communist revolution in China, Cold War polarizations, global economic and political re-orderings thereafter, burgeoning information and media flows, transformation in patterns of people movements would have played in complex ways in the phrase. It seems possible that somewhere in the interim the English usage of ‘China and the West’ has converged with the Chinese usage of ‘中国与西方’ – perhaps these have become interlingual mirror images. All that is matter for further careful study. As this blogsite on Chinese and China-related catchwords and catchphrases develops, some of those shifts may come to be considered.

I decided to pause on the phrase now, at this current juncture, because its recent employment has been quite strongly reminiscent of those 1920s uses … again? as always? I find myself increasingly struck by such resonances. Over the past few months, for instance, I read the following news stories headlining the phrase: ‘China and the West: The Gap is Set to Grow’ (Grant 5/6/2024), ‘China and the West: How Russia is Producing Weapons despite Sanctions’ (Jammine 2/5/2024), ‘Tensions Ratchet Up Between China and the West’ (Dodd 24/4/2024), ‘Solomon Islands: The Pacific Elections Being Watched Closely by China and the West’ (Mao 17/4/2024), ‘Ukraine Walks the Tightrope Between China and the West’ (Pollet 29/8/2023), ‘Can Academic Joint Ventures Between China and the West Survive?’ (Economist 20/7/2023). I have watched the BBC World documentary, China and the West: Shadow War (2024), and skimmed through the recent book Warfare Ethics in Comparative Perspective: China and the West (Twiss et al eds. 2024). These are merely very recent instances headlining the phrase; its occurrences in passing within 2023-2024 alone could make for a bulky corpus.

In such English-language texts, China is obviously neither as beleaguered a country and nor as unfamiliar a society as it had seemed in the 1920s. On the contrary, even from the headlines it is evident that China is regarded as a substantial global power. With regard to China, warlike posturing is ever in the air and the division of zones of influence appears to be at stake. Obviously too, the phrase concentrates more than ever the anxiety of contemplating a potential or actual antagonist, with an uptick of the anxieties already found in the 1920s. More interestingly, the phrase invariably continues to suggest that talking about China is a matter of confronting an ineluctable ‘civilizational’ difference. Essentially different perspectives seem to be at play, which are not to be pinned down merely by looking to material factors, ordinary political and economic calculations, general norms of social organisation.

I suspect that such essentialism has been and is invariably promoted to serve dominant vested interests and power-driven strategies. Otherwise, claims of ineluctable totalistic difference are nonsense. But it is certainly a powerful and persistent preconception, widely held, often even among the well-meaning and well-informed. It appears constantly now irrespective of where the subject-position is put in uttering ‘China and the West’ or ‘中国与西方’.

'China and the West' Chinese ver. [PDF 632KB]